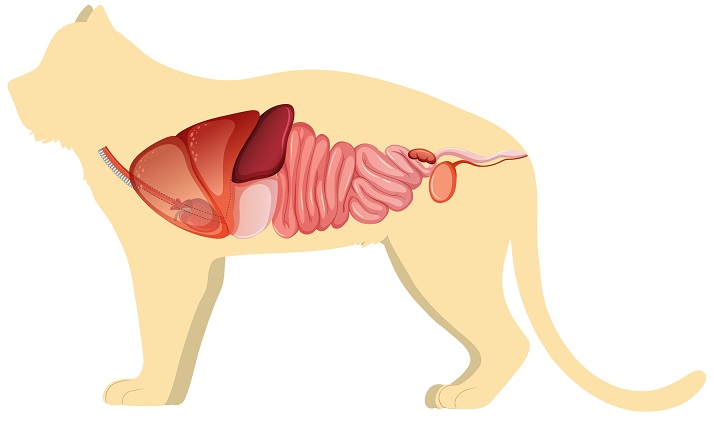

The esophagus, the forestomachs (reticulum, rumen, omasum) of ruminants, and the real stomach in all species, the small intestine, the liver, the exocrine pancreas, the large intestine, and the rectum and anus make up the digestive system. Tonsils, Peyer’s patches, and diffuse lymphoid tissue are found throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Many GI illnesses involve the peritoneum, which covers the abdominal viscera. The goal of treating GI illnesses should always be to pinpoint the ailment to a specific section and figure out what’s causing it. Then, there is a need for therapy.

Food and water prehension; mastication, salivation, and swallowing of food; food digestion and absorption of nutrients; fluid and electrolyte balancing; and waste product evacuation are the fundamental functions of the GI tract. These functions are:

- motility

- secretion

- digestion

- absorption

- blood flow

- metabolism

Peristalsis, the muscle action that propels food from the esophagus to the rectum; segmentation motions, which churn and mix the food; and segmental resistance and sphincter tone, which slow the aboral progression of gut contents, are all part of normal GI tract motility. These movements are critical for normal forestomach function in ruminants.

Pathophysiology

Reduced motility is a common symptom of abnormal motor function. The transit rate normally increases when segmental resistance is lowered. The sympathetic and parasympathetic neural systems (and consequently the activity of their central and peripheral components), as well as the GI musculature and its intrinsic nerve plexuses, stimulate motility. Atony of the gut wall is caused by debility, which is followed by muscle weakness, acute peritonitis, and hypokalemia (paralytic ileus). The intestines expand with liquids and gas, reducing fecal production. Furthermore, persistent small intestinal stasis may predispose to aberrant microbiota proliferation. By damaging mucosal cells, competing for nutrition, and deconjugating bile salts and hydroxylating fatty acids, bacterial overgrowth can cause malabsorption.

Vomiting is a neurological reaction that causes food and liquids to be ejected from the stomach through the mouth canal. It is always preceded by antecedent events such as foreboding, nausea, salivation, or shivering, and is accompanied by abdominal muscle spasms.

Passive, retrograde reflux of previously swallowed material from the esophagus, stomach, or rumen is known as regurgitation. Swallowed material may not reach the stomach due to esophageal disorders.

Distention with fluid and gas is one of the most serious outcomes of low motility. The saliva, gastric, and intestinal juices generated during regular digestion account for a large portion of the collected fluid.

Pain and reflex spasms in adjacent gut segments are caused by distention. It also encourages the production of more fluid into the gut lumen, exacerbating the problem. When distention reaches a crucial threshold, the wall’s capacity to respond deteriorates, the initial pain fades, and paralytic ileus develops, in which all GI muscle tone is lost.

GI distention can cause dehydration, acid-base and electrolyte imbalances, and circulatory failure. The accumulation of gut fluids drives increased fluid and electrolyte release in the intestine’s front regions, which can exacerbate the abnormalities and lead to shock.

Stretching of the intestinal wall is the most common cause of abdominal pain associated with GI illness. By causing direct and reactive distention of surrounding segments, gut contraction generates pain. When a peristaltic wave arrives, spasm, which is an excessive segmenting contraction of one portion of the intestine, causes distention of the immediately anterior segment. Edema and a breakdown of the local blood supply are two more causes of stomach pain (eg, local embolism or twisting of the mesentery).

Specific disorders induce diarrhea through a variety of mechanisms, which can help with understanding, diagnosing, and managing gastrointestinal ailments. Increased permeability, hypersecretion, and osmosis are the main processes of diarrhea. Motility problems are frequently secondary and lead to diarrhea. Water and electrolytes are constantly transferred across the gut mucosa in healthy animals. Secretions (from the bloodstream to the gut) and absorptions (from the gut to the bloodstream) occur in tandem. Absorption exceeds secretion in clinically healthy animals, resulting in net absorption. Inflammation of the intestines can be accompanied by an increase in the mucosa’s “pore size,” allowing more fluid to pass through the membrane (“leak”) down the pressure gradient from blood to the intestinal lumen. Diarrhea occurs when the amount expelled surpasses the intestines’ ability to absorb it. Depending on the magnitude of the increase in pore size, the size of the material that seeps through the mucosa varies. Larger pore sizes allow plasma protein to be extruded, resulting in protein-losing enteropathies (eg, lymphangiectasia in dogs, paratuberculosis in cattle, nematode infections). RBCs are lost as the pore size rises, resulting in hemorrhagic diarrhea (eg, acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome, parvovirus infection, severe hookworm infection).

Hypersecretion is a net loss of fluid and electrolytes in the intestine that occurs regardless of permeability, absorption capacity, or exogenously induced osmotic gradients. Enterotoxic colibacillosis is a type of diarrhea caused by intestinal hypersecretion, in which enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli create enterotoxin, which causes the crypt epithelium to release fluid beyond the intestines’ absorption capacity. The villi, as well as their digestion and absorption functions, are unaffected. Isotonic, alkaline, and exudate-free fluid is secreted. Even with hypersecretion, undamaged villi are advantageous because a fluid (given PO) containing glucose, amino acids, and sodium is absorbed.

When there is insufficient digestion or absorption, a collection of solutes forms in the gut lumen, causing water to be retained due to their osmotic activity. It occurs as a result of any disorder that causes nutrient malabsorption or maldigestion (eg, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency).

Malabsorption (also known as Malassimilation Syndromes in Large Animals) is the inability to absorb nutrients due to a reduction in absorption capacity, enterocyte injury, or mucosal infiltration. Several epitheliotropic viruses attack and kill villous absorptive epithelial cells and their progenitors directly (eg, coronavirus, transmissible gastroenteritis virus of piglets, and rotavirus of calves). The crypt epithelium is destroyed by feline panleukopenia virus and canine parvovirus, resulting in the failure of villous absorptive cell renewal and villi collapse; regeneration takes longer after parvoviral infection than after viral infections of the villous tip epithelium (eg, coronavirus, rotavirus). Any deficiency that reduces absorptive ability, such as diffuse inflammatory illnesses (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, histoplasmosis) or neoplasia, can cause intestinal malabsorption (eg, lymphosarcoma).

The ability of the GI tract to digest food is determined by its muscular and secretory capabilities, as well as the activity of the microbiota of ruminant forestomachs, or the cecum and colon of horses and pigs in herbivores. Ruminant flora may break down cellulose, ferment carbohydrates into volatile fatty acids, and convert nitrogenous waste into ammonia, amino acids, and protein. The activity of the flora can be inhibited to the point that digestion becomes aberrant or stops in some cases. Microbial digestion is hampered by a poor diet, prolonged famine or inappetence, and hyperacidity (as shown in grain engorgement). Oral administration of antimicrobial medications or treatments that substantially modify the pH of rumen contents can also harm bacteria, yeasts, and protozoa.

Clinical Findings of GI Disease

Signs of GI disease include:

- anorexia

- excessive salivation

- regurgitation

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- constipation

- tenesmus

- melena/hematochezia

- abdominal pain and distention

- shock and dehydration

- suboptimal performance

Recognition and examination of clinical signs can often reveal the location and nature of lesions that cause dysfunction. Furthermore, illnesses of the oral mucosa, teeth, mandible, or other bone structures of the head, throat, or esophagus are frequently connected with abnormalities of prehension, mastication, and swallowing. The most prevalent cause of vomiting in single-stomached animals is gastroenteritis or nonalimentary illness. Vomitus from a dog or cat suffering from a bleeding lesion (such as a stomach ulcer or tumor) may contain frank blood or resemble coffee grounds. Horses and rabbits are not prone to vomiting. Regurgitation is a symptom of oropharyngeal or esophageal disease that does not have the same warning symptoms as vomiting.

Hypersecretion (as in enterotoxigenic colibacillosis in newborn calves) or malabsorptive (osmotic) consequences are generally linked with large-volume, watery diarrhea. A hemorrhagic, fibrin necrotic enteritis of the small or large intestine, such as bovine viral diarrhea, coccidiosis, salmonellosis, or swine dysentery, is indicated by blood and fibrinous casts in the stools. Melena (black, tarry feces) indicates a bleed in the stomach or upper small intestine. Tenesmus of the gastrointestinal tract is generally connected with rectum and anus inflammatory illness.

Partial obstruction of the intestines can be indicated by small volumes of soft feces. The buildup of gas, fluid, or ingesta can cause abdominal distention, which is mainly caused by hypomotility (functional obstruction, adynamic paralytic ileus) or a physical obstruction (eg, foreign body or intussusception). Of course, something as simple as overeating might cause distension. A gas-filled viscus is indicated by a “ping” heard during auscultation and percussion of the abdomen. Ruminal tympany is the most common cause of significant abdominal distention in adult ruminants. When the rumen or intestines is loaded with fluid, ballottement and succussion may reveal fluid-splashing sounds. When considerable amounts of fluid are lost (e.g., in diarrhea) or sequestered, varying degrees of dehydration, acid-base, and electrolyte imbalance occur, which can lead to shock (eg, in gastric or abomasal volvulus).

Abdominal discomfort is caused by straining or inflammation of the serosal surfaces of the abdominal viscera or the peritoneum; it can be acute or subacute, and the symptoms differ depending on the species. Acute stomach pain is frequent in horses. Subacute discomfort is more common in cattle and is characterized by a lack of willingness to move, grunting with each breath, and deep abdominal palpation. Acute or subacute abdominal pain in dogs and cats is characterized by whining, meowing, and aberrant postures (eg, outstretched forelimbs, the sternum on the floor, and the hindlimbs raised). It can be difficult to pinpoint the source of abdominal pain to a specific viscus or organ.

Examination of the GI Tract

The diagnosis is frequently determined by a thorough, reliable history and a regular clinical examination. The history and epidemiologic data are critical in farm animals’ epidemics of GI tract disease. Travel history or other facts, such as recent adoption from a shelter, recent kenneling, or exposure to other animals in dog parks, may raise clinical suspicion of infectious diseases in small animals. If the history, epidemiologic, and clinical evidence point to GI disease, the lesion should be located within the system, and the nature and source of the lesion established.

History, physical examination, and fecal features can occasionally help to pinpoint whether the anomaly is in the big or small intestine. The distinction is significant because it narrows the range of possible diagnoses and directs additional inquiry. The clinician should be aware, however, that the illness can sometimes affect the entire intestine, with one set of localizing signals overshadowing the other.

The following are examples of clinical and laboratory procedures and their applications:

- visual inspection of the oral cavity and of the contour of the abdomen for distention or contraction

- palpation through the abdominal wall or per rectum to evaluate the shape, size, and position of abdominal viscera

- abdominal percussion to detect “pings,” which suggest gas-filled viscera

- auscultation to determine the intensity, frequency, and duration of GI movements, as well as fluid-splashing sounds associated with fluid-filled stomachs and intestines and fluid-rushing sounds associated with diarrheal disease

- succussion to reveal fluid-splashing sounds

- ballottement to evaluate the density and size of abdominal organs by their movement away from and back to the abdominal wall

- gross examination of feces to assess bulk, consistency, color, and presence of mucus, blood, or undigested food particles

Parasites are checked for microscopic examinations. Inflammation, neoplastic cells, or infectious disease (eg, histoplasmosis) can be detected by cytology of a rectal or colonic mucosal smear stained with fresh methylene blue or Wright stain for fecal leukocytes. The following information may be relevant (or required):

- bacterial culture and virus isolation

- therapeutic trials (eg, antibiotics or diet)

- endoscopy to visualize the mucosal surface of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, ileum, colon, or rectum

- abdominocentesis to collect fluid from distended viscera or from the peritoneal cavity for examination

- radiography (+/- contrast) to diagnose obstructive disease

- abdominal ultrasonography to evaluate the wall thickness of the stomach and intestines and to detect abdominal masses, intussusceptions, and mesenteric lymphadenopathy in small animals, and to investigate abdominal disorders in horses and cows

- biopsy (endoscopic, laparoscopic, ultrasound-guided, surgical) to obtain samples for microscopic examination

- tests for digestion and absorption to estimate and differentiate malabsorption and maldigestion (eg, serum cobalamin/folate measurement, fecal fat/starch analysis)

- tests to assess exocrine pancreatic function (serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity) and inflammation (serum canine and feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity testing).